Age:Silurian Type designation:Type section: The name “Waldron Shale” was used by N. M. Elrod (1883, p. 111) to replace the earlier designations "Waldron beds" and "Waldron fossil bed" that were used for the thinly interbedded clay, shale, and limestone overlying the quarry stone (presently known as the Laurel Member of the Salamonie Dolomite) near Waldron, Shelby County, Indiana (Shaver, 1970; Droste and Shaver, 1986). The term “Waldron” there referred to the exposure on Conns Creek in the NE¼ sec. 6, T. 11 N., R. 8 E., which was one of the locations yielding the renowned fauna of more than 200 species described by James Hall (1882) of New York State and others (Shaver, 1970; Droste and Shaver, 1986). (See Cumings, 1922, p. 453-454.) Type Waldron exposures remain at this locality in the abandoned Standard Materials Corp. quarry Indiana (Droste and Shaver, 1986). History of usage:Waldron rocks have long been known to extend along the southeastern Indiana outcrop area and into southern states (Droste and Shaver, 1986). Much later, the term “Waldron Formation” was adopted by Pinsak and Shaver (1964, p. 29) for the dominantly dolomitic facies of this unit that had been traced by that time into much of northern Indiana (Shaver and others, 1961, p. 13) except the far western counties and the northern two tiers of counties (Droste and Shaver, 1986). Several modern reports further defined northern Indiana usage and even extended recognition into adjacent western Ohio (for example, Griest and Shaver, 1982, p. 377, 379-380, and Shaver and Sunderman, 1983, p. 161-163) (Droste and Shaver, 1986). In this same period, Becker (1974, p. 18-20) defined the Waldron Shale occurrence in the more marginal part of the Illinois Basin in southwestern Indiana (Droste and Shaver, 1986).

Description:The Waldron is typically a shale containing silt and fossiliferous limestone beds that are reeflike in many places (Droste and Shaver, 1986). The terrigenous clastic content decreases westward and northward from the type area, however, so that in the southwestern subsurface, the unit becomes a dense argillaceous limestone; northwestward to its area of farthest recognition, it becomes a fairly pure dolostone bearing only shaly laminae or a faintly argillaceous appearance; and in areas in between the type area and northwestern Indiana, the Waldron consists generally of dark to mottled sublithographic to fine-grained limestone and dolostone exhibiting nodular carbonate structure in shale (Droste and Shaver, 1986).

Boundaries:The Waldron is underlain, apparently conformably but through a rather thin interval of interbedded transitional lithologies, by the Laurel Member of the Salamonie Dolomite in southern Indiana, by the undivided Salamonie in some far western counties m northern Indiana, and by the Limberlost Dolomite Member in northern Indiana (Droste and Shaver, 1986). The upper Waldron contact is also conformable, variably with the Louisville Limestone and the Louisville Member of the Pleasant Mills Formation (Droste and Shaver, 1986). This contact, however, is involved in many places with a thick transitional zone as much as a few tens of ft thick (Droste and Shaver, 1986). Correlations:Hall (1882, p. 219-220) favored a middle Niagaran age for the Waldron comparable to part of the Rochester Shale of the northeastern states and was followed in that preference by Berry and Boucot (1970, p. 249-250) and Shaver (Shaver and others, 1970, p. 187; Droste and Shaver, 1986). Physical tracing of Silurian units from the western New York standard westward across the Appalachian Basin (especially by Rickard, 1969, and Janssens, 1977) shows, however, that the Waldron must be assigned a Niagaran stratigraphic position well above that of the Rochester of western New York and also above that of the Rochester of Janssens (1977) of western Ohio. In western Ohio terms, this position is in the upper part of the Lockport Group where the upper boundary of this group has been extended upward to accommodate a westward facies change in the rocks lying above the Lockport of eastern locales in British terms its position is upper Wenlockian (Droste and Shaver, 1986).

Economic Importance:Industrial Minerals: Crushed stone products from the Waldron Formation, Shale, Member (Silurian) include the following: aglime, base materials, chemical uses, crushed stone, dolomite limestone, fill materials, high-calcium limestone, hot and cold mix asphalt, pugmill materials, riprap, and manufactured sand from quarries in Adams, Blackford, Clark, Delaware, Grant, Hamilton, Huntington, Rush, Scott, Shelby, Wabash, and Wells Counties (Shaffer, 2016). |

|

Regional Indiana usage:

Illinois Basin (COSUNA 11)

Misc/Abandoned Names:Waldron beds, Waldron fossil beds Geologic Map Unit Designation:Swl Note: Hansen (1991, p. 52) in Suggestions to authors of the reports of the United States Geological Survey noted that letter symbols for map units are considered to be unique to each geologic map and that adjacent maps do not necessarily need to use the same symbols for the same map unit. Therefore, map unit abbreviations in the Indiana Geologic Names Information System should be regarded simply as recommendations. |

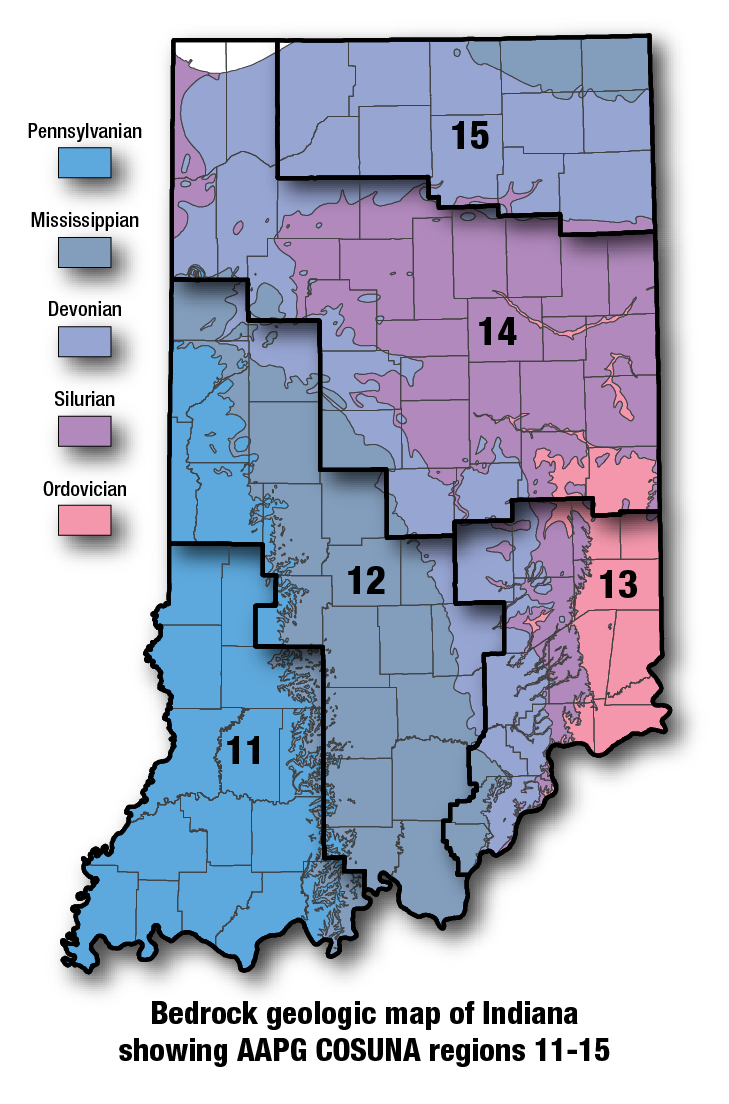

COSUNA areas and regional terminologyNames for geologic units vary across Indiana. The Midwestern Basin and Arches Region COSUNA chart (Shaver, 1984) was developed to strategically document such variations in terminology. The geologic map (below left) is derived from this chart and provides an index to the five defined COSUNA regions in Indiana. The regions are generally based on regional bedrock outcrop patterns and major structural features in Indiana. (Click the maps below to view more detailed maps of COSUNA regions and major structural features in Indiana.)

COSUNA areas and numbers that approximate regional bedrock outcrop patterns and major structural features in Indiana.

Major tectonic features that affect bedrock geology in Indiana. |

References:Berry, W. B. N., and Boucot, A. J., 1970, Correlation of the North American Silurian rocks: Geological Society of America Special Paper 102, 289 p. Cumings, E. R., 1922, Nomenclature and description of the geological formations of Indiana, in Logan, W. N., Cumings, E. R., Malott, C. A., Visher, S. S., Tucker, W. M., Reeves, J. R., and Legge, H. W., Handbook of Indiana geology: Indiana Department of Conservation Publication No. 21, pt. 4, p. 403–570. Elrod, M. N., 1883, Geology of Decatur County: Indiana Department of Geology and Natural History Annual Report 12, p. 100–152. Griest, S. D., and Shaver, R. H., 1982, Geometric and paleoecologic analysis of Silurian reefs near Celina, Ohio: Indiana Academy of Science Proceedings, v. 91, p. 373–390. Hall, James, 1882, Descriptions of the species of fossils found in the Niagara Group at Waldron, Indiana: Indiana Department of Geology and Natural Resources Annual Report 11, p. 217–345. Hansen, W. R., 1991, Suggestions to authors of the reports of the United States Geological Survey (7th ed.): Washington, D.C., U.S. Geological Survey, 289 p. Janssens, Adriaan, 1977, Silurian rocks in the subsurface of northwestern Ohio: Ohio Geological Survey Report of Investigations 100, 96 p. Rickard, L. V., 1969, Stratigraphy of the Upper Silurian Salina Group, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Ontario: New York State Museum and Science Service Geological Survey Map and Chart Ser. 12, 57 p. Shaver, R. H., coordinator, 1984, Midwestern basin and arches region–correlation of stratigraphic units in North America (COSUNA): American Association of Petroleum Geologists Correlation Chart Series. |

|

For additional information, contact:

Nancy Hasenmueller (hasenmue@indiana.edu)Date last revised: February 12, 2016