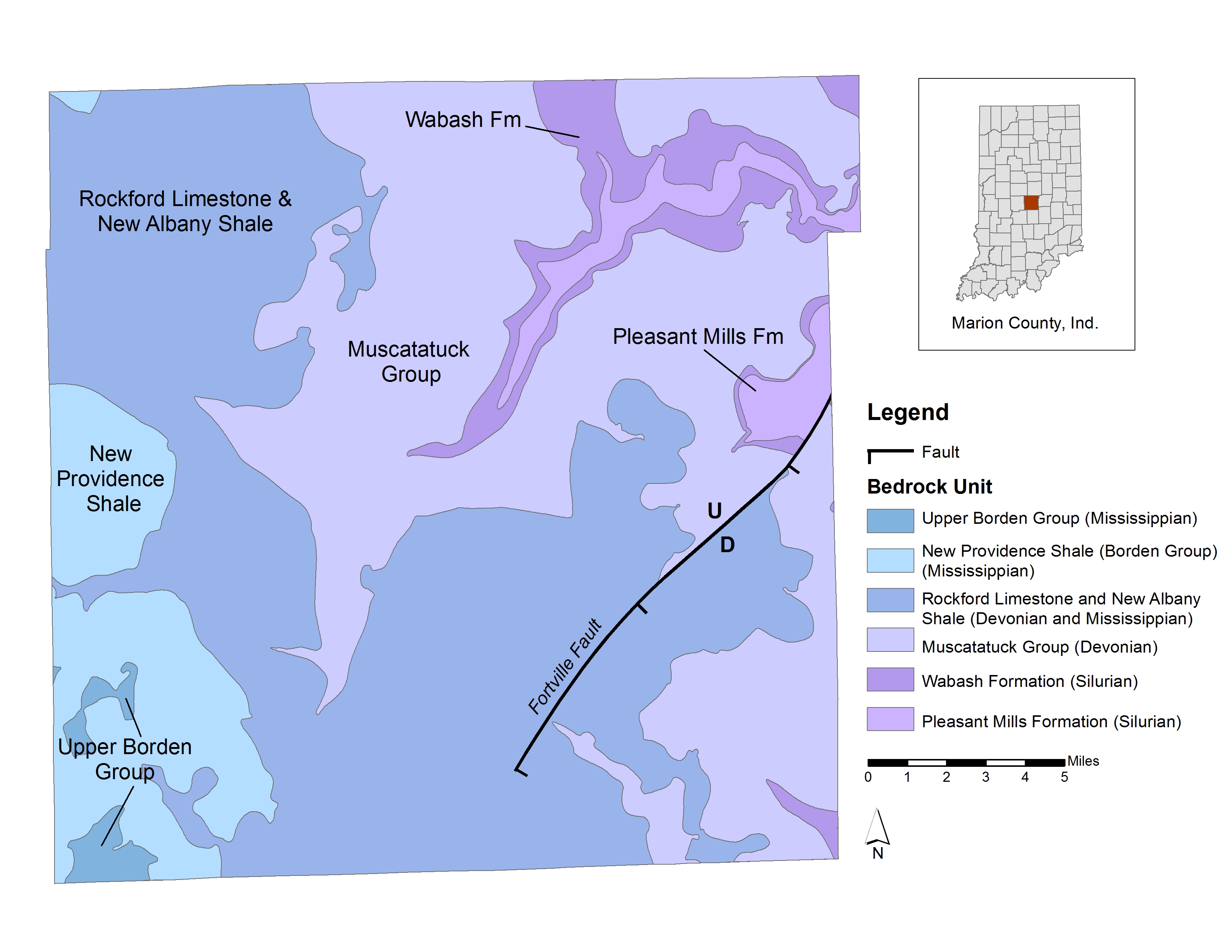

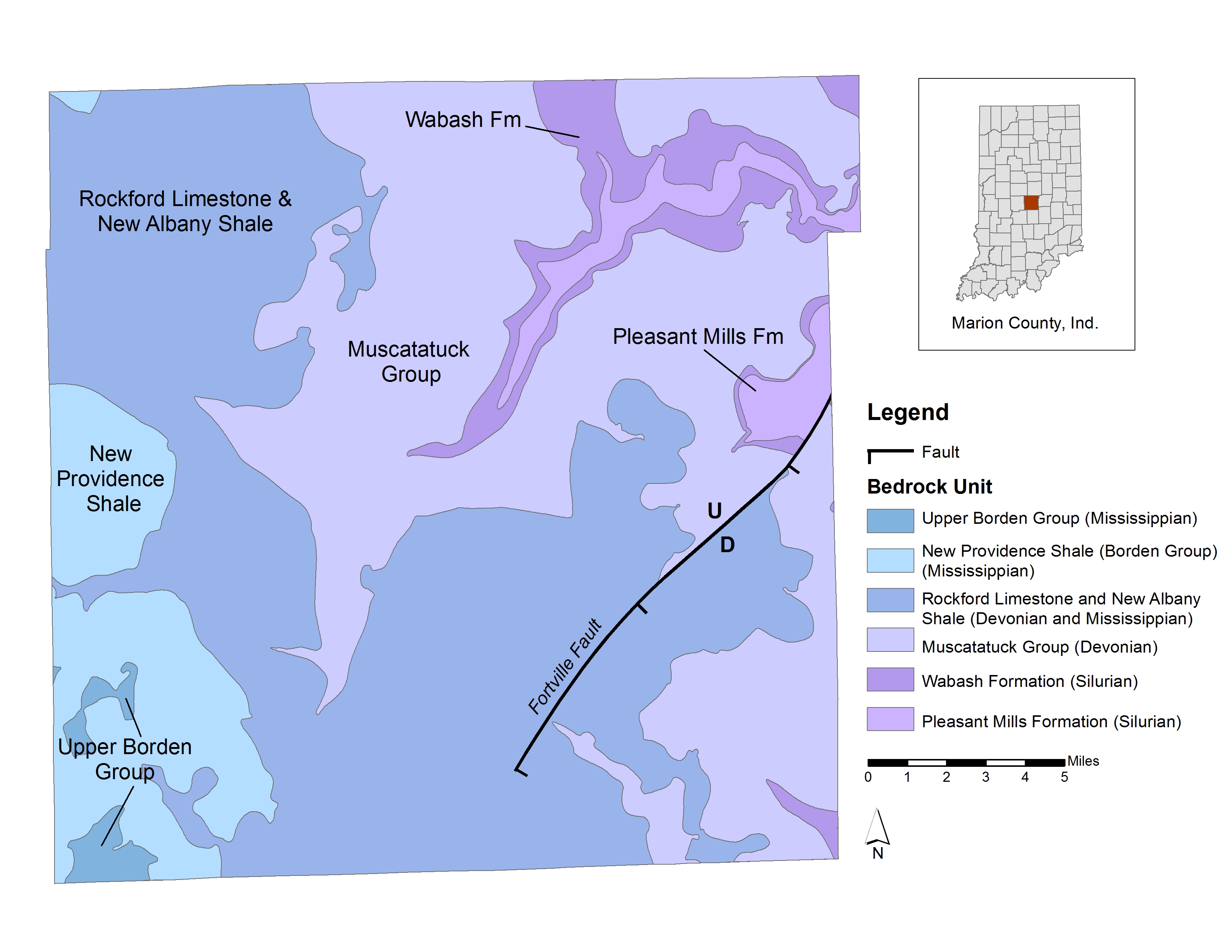

Figure 1.

Map showing the bedrock geology of Marion County (modified from Hasenmueller, 2003a, b).

The bedrock surface in Marion County is composed of

Paleozoic stratigraphic units ranging from

Silurian to

Mississippian age (Hasenmueller, 2003a, b) (fig. 1).

These units are composed of shales,

siltstones,

sandstones,

limestones, and

dolostones.

The relief on this bedrock surface is more than 300 ft (91.4 m), with elevations ranging from 505 to 808 ft

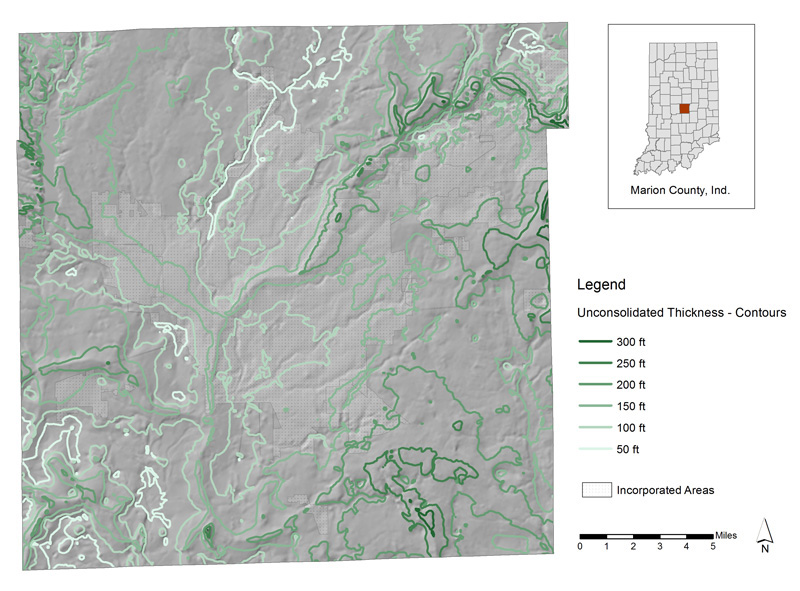

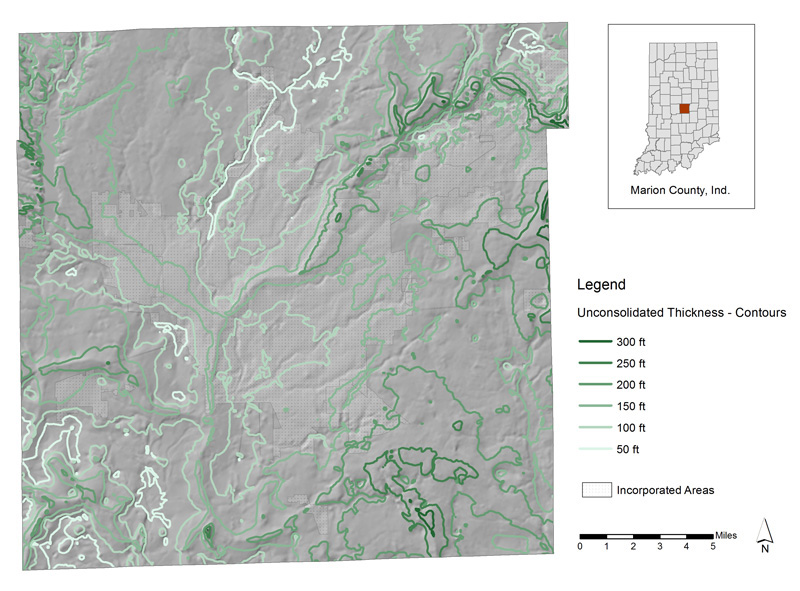

(153.9 to 246.3 m) (Hasenmueller and James, 2003a, b) (fig. 2). The bedrock surface is mantled by

unconsolidated

deposits that range in thickness from a few feet to more than 300 ft (91.4 m) (Fleming, Brown, and Ferguson,

2000; James and Hasenmueller, 2003a, b) (fig. 3). Typical depths to bedrock are in excess of 100 ft (30.48 m)

over most of the county. Fleming, Brown, and Ferguson (2000) noted that the bedrock is exposed naturally only

in two small areas, one being along the White River in Broad Ripple (Indianapolis West quadrangle), and the

second in the extreme southwestern part of the county near the Village of West Newton (Bridgeport quadrangle).

Because the bedrock surface cannot be directly observed, its topography and geology were inferred from petroleum

and water well records, gamma-ray logs, seismic records, and other sources of subsurface information (Fleming,

Brown, and Ferguson, 2000; Hasenmueller, 2003a, b; Hasenmueller and James, 2003a, b).

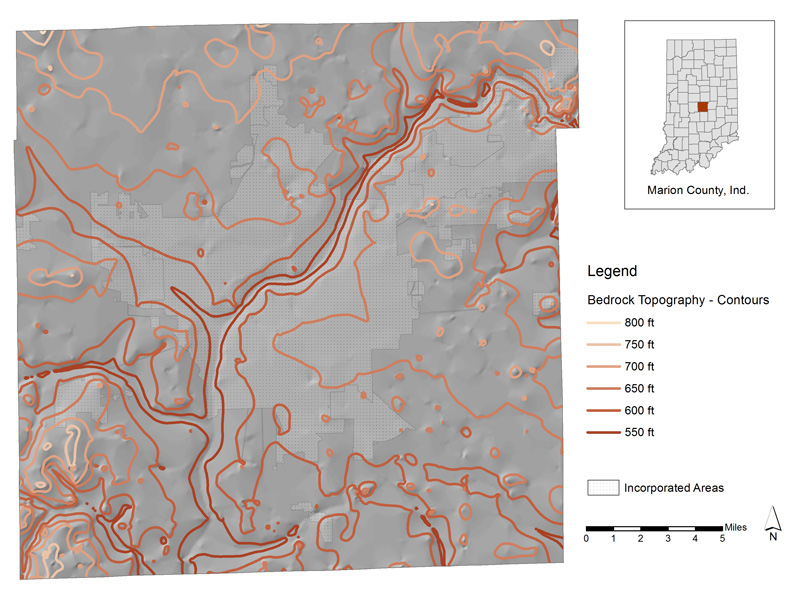

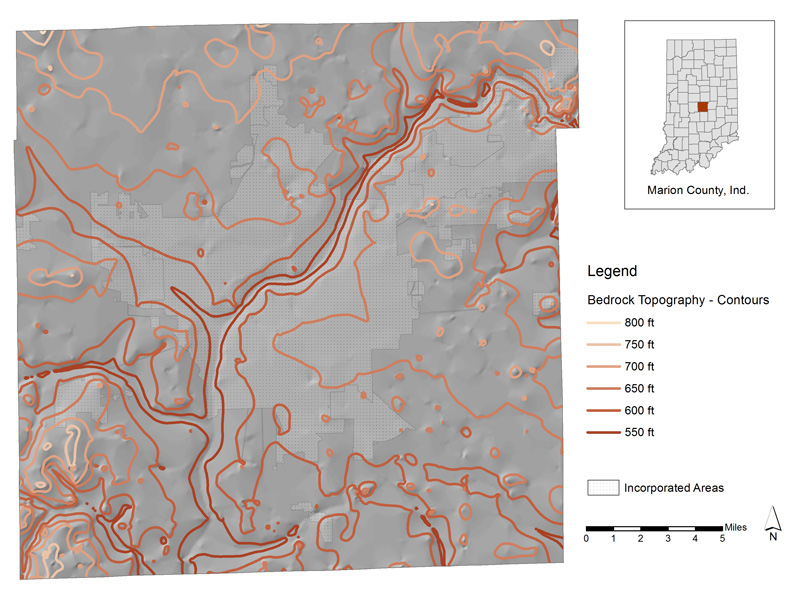

Figure 2.

Map showing the bedrock elevation of Marion County (modified from Hasenmueller and James, 2003a, b). Contour interval is 50 ft (15.2 m).

The lowest bedrock elevations are within a deeply entrenched bedrock valley system in the northeastern part of

Marion County, whereas the highest elevations occur along bedrock ridges associated with the buried

Knobstone Escarpment

in the southwestern part of the county (Fleming, Brown, and Ferguson, 2000). The pattern of relief

on the bedrock surface reflects several pre-glacial or interglacial valley systems superposed on broader

physiographic regions

controlled by the general resistance of particular types of bedrock to erosion (Fleming,

Brown, and Ferguson, 2000). For example, much of the bedrock surface underlain by the

Devonian and Mississippian

shales of the New Albany Shale forms a broad, rolling lowland that contains the axes of one or more major bedrock

valleys. In contrast, the bedrock surface formed on the resistant siltstones and sandstones of the Mississippian

Borden Group exhibits more than 250 ft (76.2 m) of local relief, characterized by sharp ridge crests adjacent to

narrow, deep valleys (Fleming, Brown, and Ferguson, 2000). A rolling plateau, cut by several canyonlike valleys

and containing locally abundant sinkholes, is characteristic of the bedrock surface on the Silurian and Devonian

carbonates (Fleming, Brown, and Ferguson, 2000).

Figure 3.

Map showing the thickness of unconsolidated material in Marion County (modified from James and Hasenmueller, 2003a, b,). Contour interval is 50 ft (15.2 m).

The bedrock surface appears to have been modified by glacial activity, particularly that of channelized

meltwater.

Fleming, Brown, and Ferguson (2000) reported that most of the bedrock uplands have, at one time or another,

undergone direct erosion by glacial ice, whereas some of the bedrock lowlands may have been protected from

glacial scouring and remain largely unchanged from their pre-glacial configuration. Some of the larger bedrock

valley systems, however, may have been greatly modified, and some were perhaps cut in their entirety, by torrents

of meltwater (Fleming, Brown, and Ferguson, 2000). Although the details of this history are mostly obscured by the

overlying glacial deposits, the general pattern of repeated scouring and filling of some bedrock valleys is

abundantly clear on the basis of such evidence as cross-cutting

thalwegs, breached

drainage divides, inset fill

stratigraphy, and cross-cutting

outwash channels of vastly different ages (Fleming, Brown, and Ferguson, 2000).

The bedrock surface formed on the Silurian and Devonian carbonate rocks is characterized by relict

karst

(Fleming, Brown, and Ferguson, 2000). Karst features are not directly observable in most of Marion County

except in quarry exposures and underground limestone mines. Karst features, including sinkholes, small caves,

and other solution features, are abundant in the exposures of Silurian and Devonian carbonate rocks in

southeastern Indiana (Powell, Frushour, and Harper, 2002).

References

Fleming, A. H., Brown, S. E., and Ferguson, V. R., 2000, Geologic and hydrogeologic framework, in Brown, S. E., and Laudick, A. J., eds., 2003, Hydrogeologic framework of Marion County, Indiana-a digital atlas illustrating hydrogeologic terrain and sequence: Indiana Geological Survey Open-File Study 00-14, CD-ROM.

Hasenmueller, W. A., 2003a, Bedrock geologic map of the Indianapolis 30 x 60 minute quadrangle, central Indiana: Indiana Geological Survey Open-File Study 03-07, scale 1:100,000.

Hasenmueller, W. A., 2003b, Bedrock geologic map of the west half of the New Castle 30 x 60 minute quadrangle, central Indiana: Indiana Geological Survey Open-File Study 03-10, scale 1:100,000.

Hasenmueller, W. A., and James, C. L., 2003a, Map showing elevation of the bedrock surface in the Indianapolis 30 x 60 minute quadrangle, central Indiana: Indiana Geological Survey Open-File Study 03-03, scale 1:100,000.

Hasenmueller, W. A., and James, C. L., 2003b, Map showing elevation of the bedrock surface in the west half of the New Castle 30 x 60 minute quadrangle, central Indiana: Indiana Geological Survey Open-File Study 03-06, scale 1:100,000.

James, C. L., and Hasenmueller, W. A., 2003a, Map showing thickness of the unconsolidated deposits in the Indianapolis 30 x 60 minute quadrangle, central Indiana: Indiana Geological Survey Open-File Study 03-11, scale 1:100,000.

James, C. L., and Hasenmueller, W. A., 2003b, Map showing thickness of the unconsolidated deposits in the west half of the New Castle 30 x 60 minute quadrangle, central Indiana: Indiana Geological Survey Open-File Study 03-14, scale 1:100,000.

Powell, R. L., Frushour, S. S., and Harper, Denver, 2002, Distributions of sinkholes, sinking-stream basins, and cave openings in southeastern Indiana: Indiana Geological Survey Miscellaneous Map 64, scale 1:250,000.