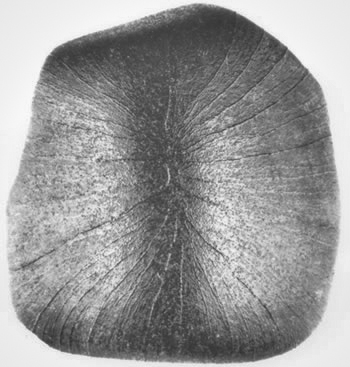

Cut surface of the LaPorte County meteorite.

Meteorites are rocks that fall to Earth from outer space. They have fascinated mankind since the beginning of time. They are scientifically valuable objects that help geologists understand the origins of planets and the processes that shape the Earth. Meteorites are rare and they exhibit special features that differentiate them from Earth rocks.

Among characteristics that identify meteorites are a high specific gravity (especially true for irons); a dark color; and a dark glassy or dull crust if fresh or a rind of iron oxide (rust) if weathered. Most meteorites attract a magnet, although some only slightly. Many show aerodynamic shape, and their crusts may be marked with flow structures or shallow depressions called "thumbprints".

The Lafayette meteorite exhibits flow structures.

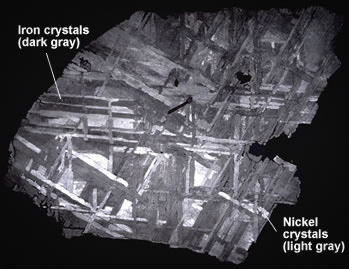

Chondrules are almost certain proof that an object is a meteorite. A mixture of nickel and iron that appears as bright metallic flecks in a stone, or that makes up most of the object, also is a positive indicator. The Widmanstatten pattern (see LaPorte meteorite image) is also further proof.

Many tests needed to verify the identity of a meteorite should be performed by an experienced scientist, as much of the scientific information can be lost if the meteorite is improperly handled.

Iron meteorites are mainly made of the nickel-iron minerals kacacite and taenite. But they may also contain other minerals and metals, such as cobalt, copper, and zinc.

Stoney irons consist of about 50 percent nickel and iron and 50 percent silicate minerals. They are of two types: the pallasites and the mesosiderites. Pallasites have large (5-10 mm) glassy grains of olivine in a continuous matrix of nickel-iron. Mesosiderites contain small, bright, irregularly distributed metal flecks in a matrix of plagioclase and pyroxene minerals. Despite their apparent similarity, pallasites and mesosiderites appear to have different histories.

This specimen exhibits shallow depressions called thumbprints.

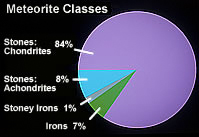

Stone meteorites are mineralogically the most complex and are the most abundant. They are dominantly made of silicates. Two main types—chondrites and achondrites—are recognized.

Chondrites, the most common (84 percent of falls), contain small (less than 1/8 inch) structured spheres called chondrules. Chondrules are found only in meteorites and contain some of the oldest material known to Man. Their origin is still uncertain, despite many theories proposed to explain them.

Achondrites—the second type of stone meteorites—contain silicates but do not contain chondrules. They resemble basalt from the Earth and represent about 8 percent of falls.

Where meteorites have been recovered in Indiana..

Many rocks and manmade objects appear similar to meteorites. Some suspected meteorites that proved not to be meteorites when examined closely at the Indiana Geological Survey were igneous rocks left by glaciers, sedimentary rock concretions, metallic alloys, and pieces of silicon. Even materials fused together by trash fires can resemble meteorites.

*Meteorites that are seen as they fall and are recovered shortly after landing are classed as falls; those that are accidently found long after falling are classed as finds.

What to Look for in a Meteorite

- Thin, dark glassy-to-dull coating or fusion crusts

- Flow structures or "thumbprints" on outside

- Aerodynamic shape

- High specific gravity

- Metallic nickel-iron

- Widmanstatten pattern

- Small spherical chondrules

- Attracts magnets

The Hangman's Crossing meteorite exhibits features that are indicators of meteorites.

Think you may have a meteorite?

Members of the public are always welcome to bring rocks and minerals to our Bloomington office for more information, but the IGWS is unable to inspect or evaluate suspected meteorites. For more information on meteorite authentication and testing, please contact the Field Museum, Washington University in St. Louis, or the University of California, Los Angeles.

Indiana Meteorites

Click linked names to see larger views.

| Name | County | Fall or Find* | Date | Type | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hamlet | Starke | Fall | Oct. 13, 1959 | Chondrite | Struck a house |

| Hangman's Crossing | Jackson | Find | 1987 | Chondrite | |

| Harrison County | Harrison | Fall | March 28, 1859 | Chondrite | Shower with only 4 stones recovered |

| Helt Township | Vermillion | Fall | 1883-1884 | Iron | |

| Kokomo | Howard | Find | 1862 | Iron | |

| Lafayette | Tippecanoe | Find | 1931? | Achondrite | Found in collection at Purdue Univ. |

| LaPorte | LaPorte | Find | 1900 | Iron | Large piece buried and lost |

| Noblesville | Hamilton | Fall | Aug. 31, 1991 | Chondrite | Nearly struck a boy |

| Plymouth | Marshall | Find | 1893 | Iron | Large piece buried and lost |

| Rochester | Fulton | Fall | Dec. 21, 1876 | Chondrite | Only piece from large fireball |

| Rush County | Rush | Find | 1948 | Chondrite | |

| Rushville | Franklin | Find | 1866 | Chondrite | Previously known as Brookville; renamed in 1903 |

| South Bend | St. Joseph | Find | 1915 | Stoney Iron (Pallasite) |