The Pleistocene Ice Age

The central Indiana landscape is primarily a product of the

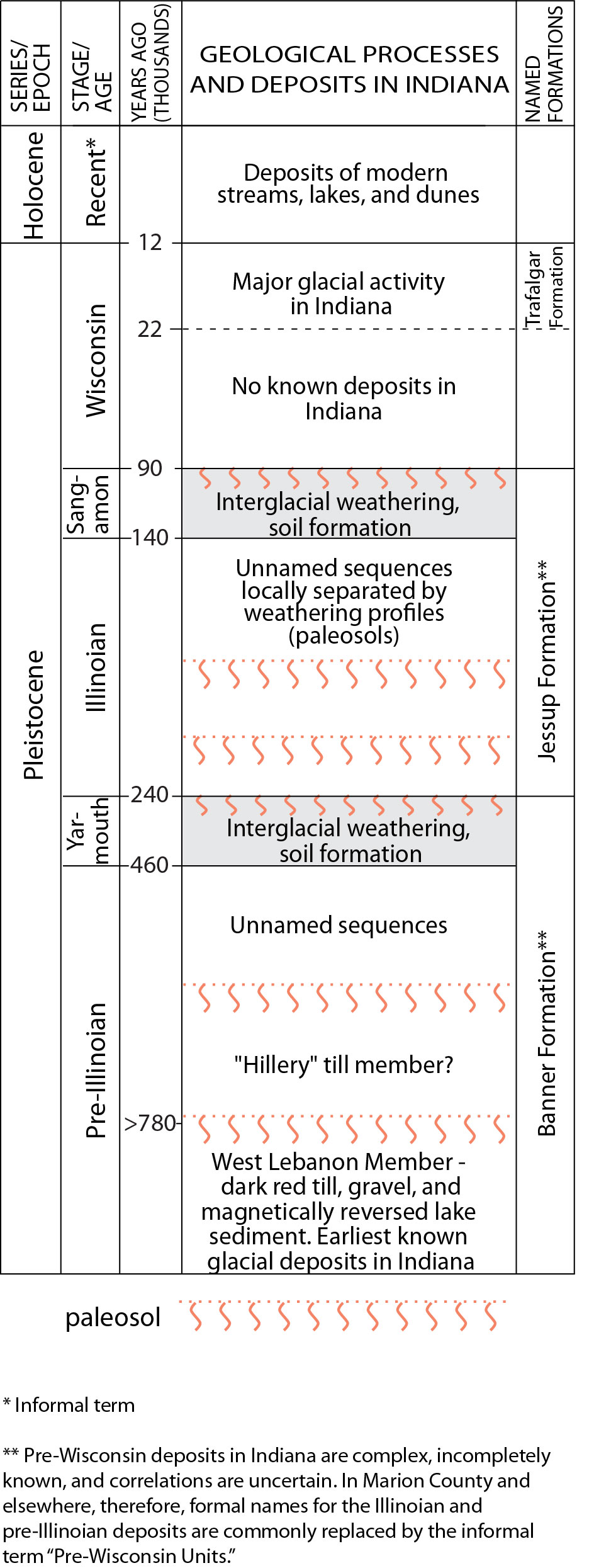

Figure 1.

Pleistocene deposits in Marion County are broadly grouped into

three main periods — the

The Ice Age was punctuated by several prolonged warm periods during which the glaciers disappeared entirely from the temperate latitudes and a climate similar to today or even warmer prevailed. The interglacial landscape was modified by typical terrestrial processes, such as erosion by streams to produce hills and valleys, and deep soil development; it also supported abundant vegetation, including hardwood forests and wetlands similar to those present today. These warmer periods are known as interglacial stages (fig. 1), and they separate several major stages of glacial advance that are recorded by the Pleistocene deposits in the Midwest.

Indirect geophysical evidence suggests that the core of the Laurentide Ice Sheet in the vicinity of southern Canada and the Great Lakes was up to 2 miles (3.2 km) thick, similar to the modern Greenland ice cap. The thickness of the glacial lobes that affected central Indiana is less clear, but was probably several thousand feet at times, with progressively thinner ice toward the margin of the glacier. In general, deposition occurs near the margin of glaciers, whereas erosion is the dominant process further back up-ice — especially beneath the cores of large ice sheets, where the substrate beneath the glacier may be severely scoured, completely removing any earlier glacial deposits that may have been present, and deeply eroding the underlying bedrock. Topographic characteristics of the substrate also greatly affect where erosion and deposition occur, with hills and other obstructions often experiencing intense erosion, while valleys and lowlands typically are sites of deposition where earlier deposits tend to be well preserved (see How Glaciers Work).

Unconsolidated Deposits

The modern landscape of Marion County, and the unconsolidated deposits within about 30 to 50 ft (9 to 15 m) of the surface, are chiefly the

product of the most recent stage of glaciation, called the late Wisconsin, which affected the county between about 22,000 and 17,000 radiocarbon

years B.P. At many places, however, the

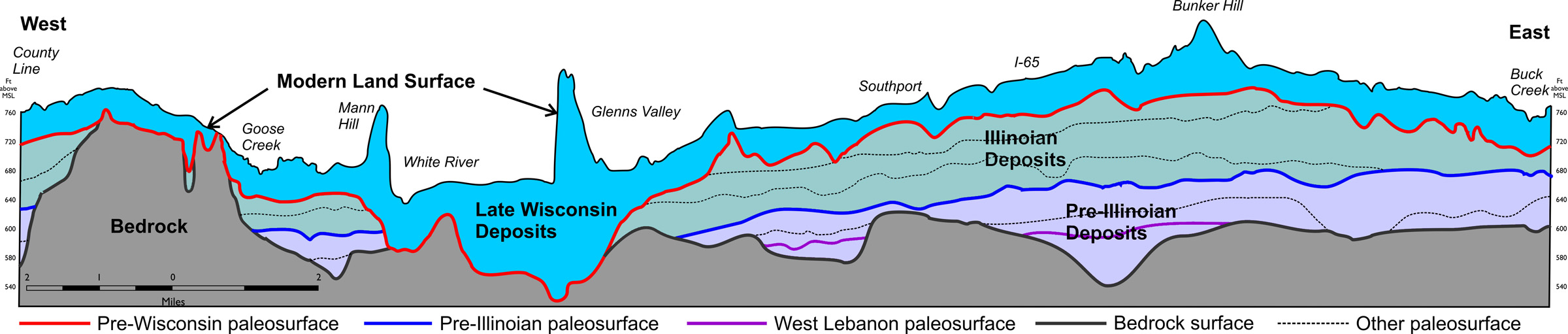

Figure 2.

Simplified west-to-east geologic cross section illustrating the relationship of the topography of the bedrock surface and the modern land surface

to the total thickness of unconsolidated sediments. The diagram also illustrates the complicated cross-cutting relations between several major and

minor paleosurfaces (ancient landscapes typically represented by weathering horizons and changes in geologic properties) that bound the different

glacial sequences beneath the county. (Adapted from cross sections in Brown and Laudick, 2003).

Figure 3.

The Indianapolis skyline, as seen from the summit of Crown Hill. Crown Hill is a kame—a mound of sand and gravel — that stands more than 60 ft

(18.3 m) above its immediate surroundings, and nearly 150 ft (45.7 m) above the nearby White River. It formed along a late Wisconsin end moraine.

Photo by A. H. Fleming.

These examples demonstrate the close relationship between the thickness of glacial deposits and the underlying bedrock topography: glacial

deposits are almost invariably thicker and better preserved in low areas on the bedrock surface, such as buried valleys, whereas they are

usually much thinner over bedrock highs, such as that in the southwestern part of the county (fig. 2). Certain kinds of glacial deposits,

such as end

Pleistocene History and Glacial Terrains of Marion County

Figure 4.

The gorgelike valleys of several of the larger streams are among the youngest glacial landforms in the county. They were cut about 17,000 years

ago by voluminous

The landscape of Marion County is made up of a series of glacial terrains, each characterized by a specific set of landforms and underlying

sedimentary sequences that reflect a particular geologic history and set of depositional (or erosional) processes local to that region of the

landscape. These terrains are primarily the result of late Wisconsin glaciers active in the county from about 22,000 to 17,000 radiocarbon

years B.P., and the meltwater they produced (fig. 4). Late Wisconsin sequences average about 50 to 75 ft (1.5 to 22.9 m) thick in the county,

but are locally much thicker or thinner, depending on the type of terrain they form and the relief on underlying deposits and bedrock. These

deposits are widely exposed at the surface, cropping out in bluffs, along stream banks, and in many excavations almost anywhere in the county,

thus they are readily observed and relatively well known. Among other things, they form the parent materials for the surface soil, act as the

foundation for most infrastructure, and contain major

At many places, however, the Late Wisconsin sequences make up only a fraction of the total glacial deposits present above bedrock, and are draped over

thick sequences of Illinoian and pre-Illinoian age sediments that collectively are referred to as "

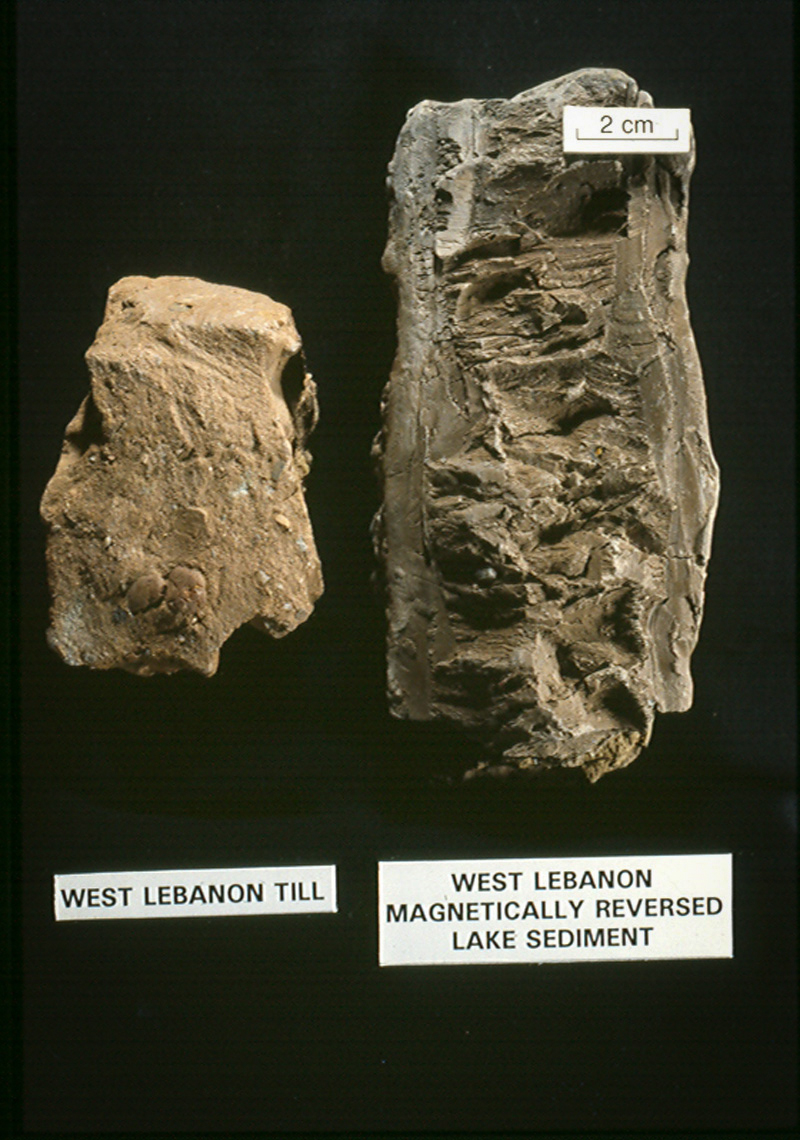

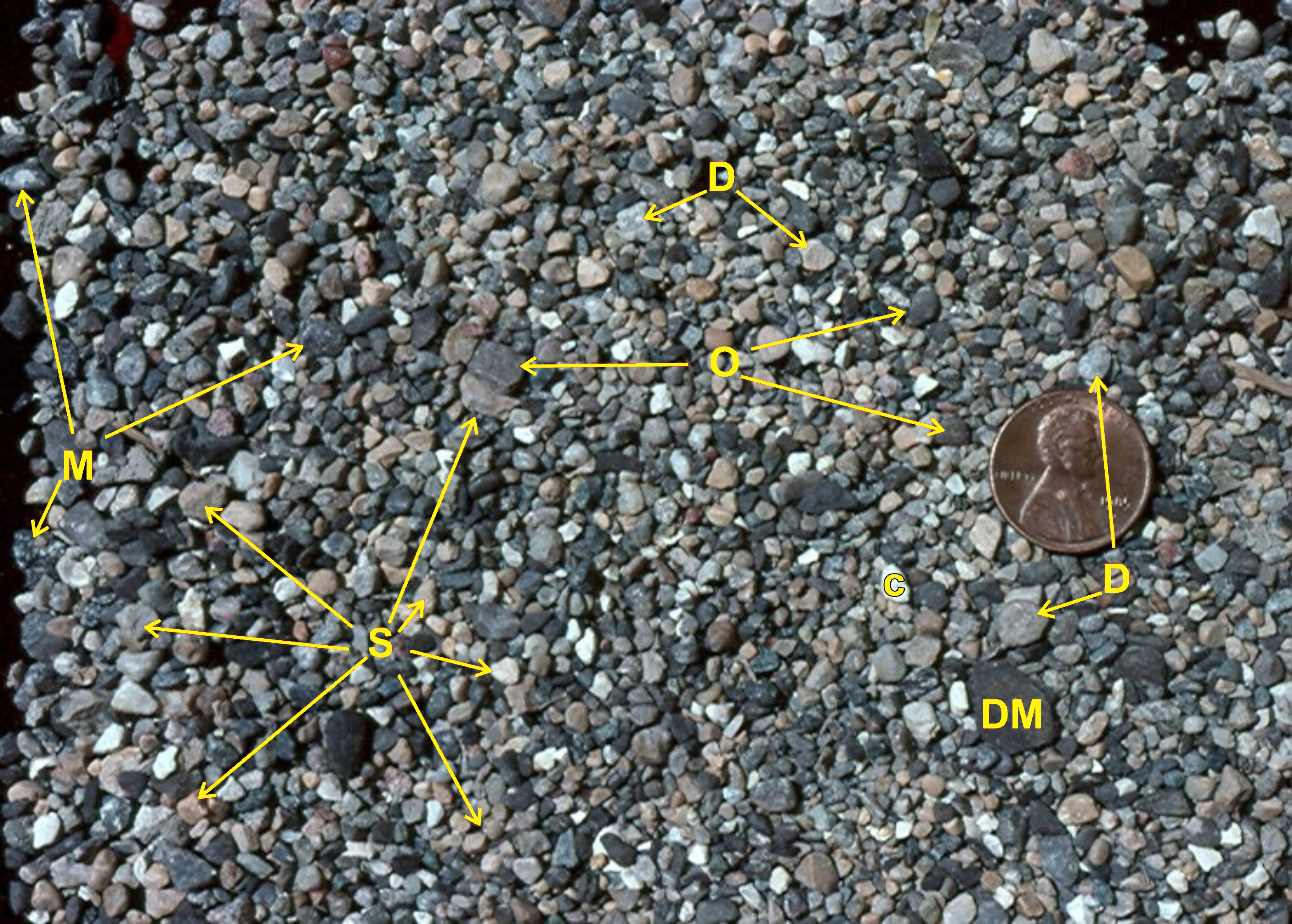

Figure 5.

Samples of West Lebanon till and lake sediment.

Pre-Wisconsin History and Sequences

The oldest glacial deposits in the county (fig. 5) consist of a series of reddish-brown, clay-rich lake sediments,

Figure 6.

Unweathered Illinoian till overlies a several-yards (meters) thick, bright orange-brown paleosol on pre-Illinoian sediment at Cagles Mill in Putnam

County. The light-colored areas are

At least two other major pre-Illinoian glaciations are recognized in the deposits beneath Marion County. One, represented by a series of pinkish tills and associated sand and gravel, was deposited by ice flowing into Indiana from the northeast and probably correlates with the so-called "Hillery Till Member" of eastern Illinois (Johnson and others, 1972; Bleuer, 1991). In contrast, the top of the pre-Illinoian section consists of a thick sequence of weathered sand and gravel deposits interbedded with olive-gray sandy till. This interval is an important deep aquifer at many places in the county and is commonly recognizable by the strong interglacial weathering profile formed on its surface (fig. 6). Although evidence of weathering profiles locally occurs within and between all of the pre-Illinoian sequences, none are as pronounced or as widely recognizable as the one at the top of the section, which is marked by a reddish or olive-colored buried soil profile more than 20 ft (6.1 m) thick in some boreholes. This weathering horizon is believed to have formed mainly during the Yarmouth interglacial stage, prior to 200,000 years ago, and represents the interglacial landscape that existed just prior to the Illinoian glaciation.

Much of the pre-Wisconsin section beneath Marion County consists of a series of at least four, hard, gray-brown, loam-textured Illinoian tills deposited between 200,000 and 130,000 years ago (fig. 7). The tills are mostly similar in appearance and difficult to distinguish without detailed chemical and mineralogical analyses, which suggest that at least two of the tills were deposited by glaciers that came from the northeast, while another was deposited by ice that advanced out of Michigan. These till sheets are, however, locally separated from one another by variably eroded weathering horizons that exhibit loss of carbonate minerals, strong jointing, and olive-brown paleosols a few feet thick. Illinoian glaciers advanced as far as the Ohio River valley and northern Kentucky — further south than any other Pleistocene glaciation in Indiana — resulting in significant erosion of earlier deposits by each successive ice advance that came over Marion County. The Illinoian tills are also separated at places by thin, discontinuous lenses and some larger bodies of sand and gravel, the largest of which form extensive sheet-like bodies in the southern part of the county, where they serve as important groundwater sources.

Figure 7.

Pinkish-gray Illinoian till along Indian Creek near McCordsville. The pink color is from weathering. The till is systematically jointed, with the

two most prominent sets oriented at 60o to the till fabric (parallel to blue needle). Needle is 25 cm long. Photo by A. H. Fleming.

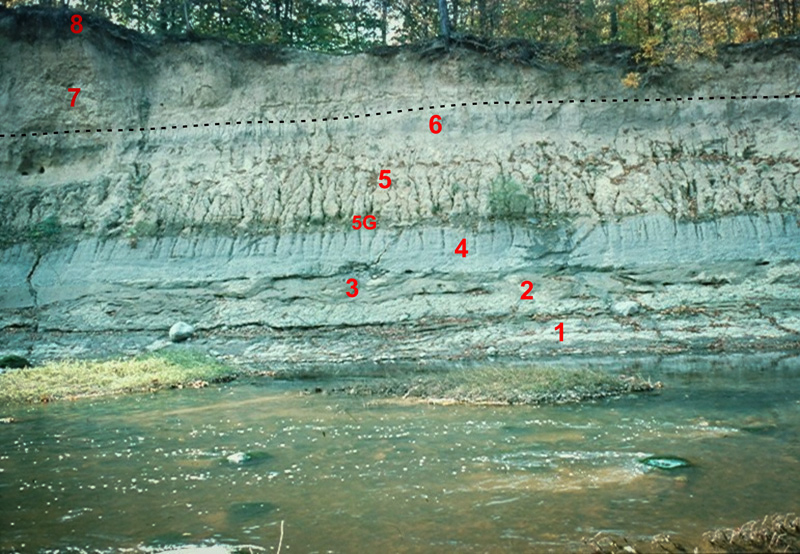

The tendency of later ice advances to modify and erode the older deposits they advanced over has produced complex subsurface relations among the various pre-Wisconsin sequences, characterized by numerous cutouts of older sequences and paleosurfaces by younger ones. Large, outwash-filled buried valleys localized within the glacial section are fairly common, and may or may not exhibit any relationship to buried valleys or other topographic features associated with the bedrock surface. These relations, along with the limited number of surface exposure, hinder systematically sorting out the character, continuity, and history of these ancient deposits at any except the most local scale. More extensive exposures of pre-Wisconsin deposits elsewhere in the state (for example, fig. 8) offer additional clues as to their character and complex history, and serve as a useful analogue for the subsurface of Marion County. A more comprehensive treatment of the pre-Wisconsin deposits of Marion County can be found here.

Figure 8.

A complicated series of old glacial deposits underlies the pre-Wisconsin surface in this exposure along Wildcat Creek in Clinton County. Well-jointed,

pink, crudely layered pre-Wisconsin till (1) is separated from overlying massive greenish-gray till (2) by a thin layer of gravel and dark silt. Both

till units have strong fabrics, oriented in sharply different directions, indicating the tills came from different sources. Unit 3 is a sheared and

folded, discontinuous body of sandy silt that appears to fill depressions in unit 2. It is overlain

The Pre-Wisconsin Surface

Figure 9.

Dark brown organic silt with fragments of spruce wood (arrows) overlies weathered orange-brown Illinoian till along the pre-Wisconsin surface in this

exposure at Geist Reservoir. The silt was deposited, possibly by wind, in a boreal wetland that was overrun by late Wisconsin ice. Late Wisconsin T1

till overlies the silt along the dashed line near the top of the frame. Field of view is about 5 ft (1.5 m) wide. Photo by A. H. Fleming.

Despite these complications, or perhaps because of them, the most readily recognizable horizon associated with the pre-Wisconsin deposits below Marion

County is the paleosurface (fig. 9) that developed during the

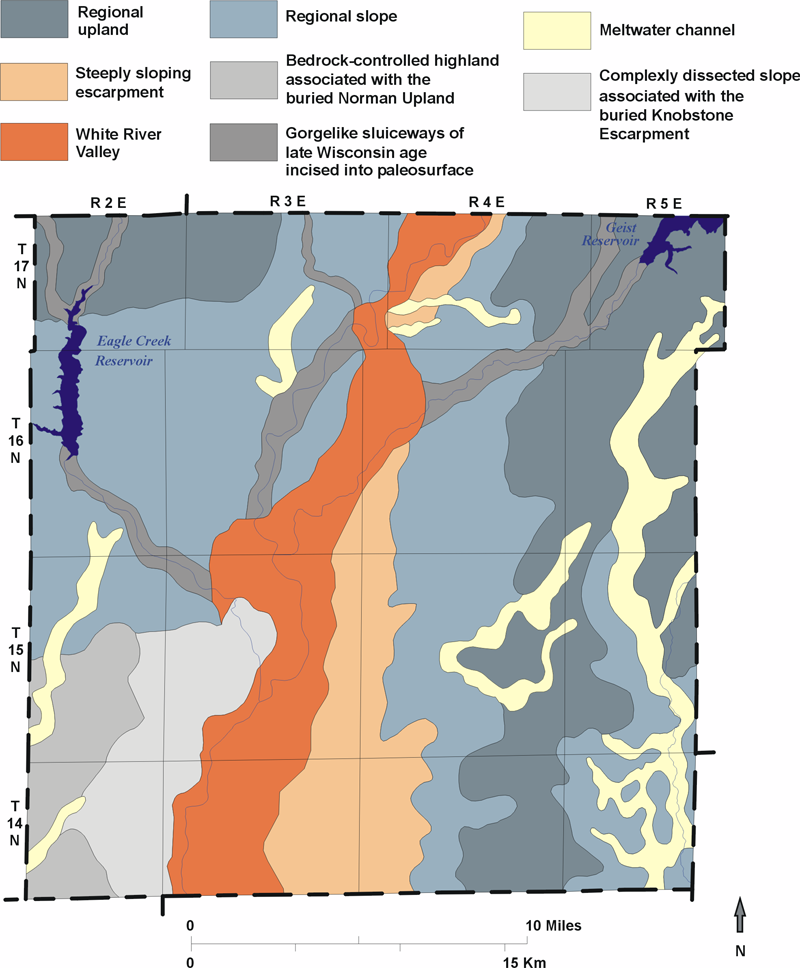

Figure 10.

Major physiographic features of the pre-Wisconsin surface in Marion county.

Figure 10 shows a simplified map of the major

Late Wisconsin History and Terrains: Origin of the Modern Landscape

The late Wisconsin Laurentide Ice Sheet began to affect Marion County and surrounding areas approximately 22,000 years ago with the arrival of large volumes of meltwater that were carried down the already well-established White River valley from the ice front, which lay north of the county. Over the next 1,000 years, the ice sheet advanced into and eventually covered all of Marion County as it established a terminal position well to the south in Morgan and Johnson Counties. Radiocarbon ages from wood at the base of the Wisconsin section in northwestern Marion County indicate that glacial conditions were well established in that part of the county no later than 21,000 radiocarbon years B.P.

Figure 11.

Borehole sample of

All of the late Wisconsin sequences in Marion County are members of the Trafalgar Formation (Wayne, 1963), which is named for the small Johnson County

village where these deposits were first described. The Trafalgar Formation is the principal surface unit throughout the central till plain and was

deposited by ice flowing out of the Huron-Erie Basin. It has a distinctive eastern source mineralogy, characterized by a high concentration of calcite

(limestone) in the silt and sand fraction, as well as abundant fragments of

The Trafalgar Formation, as currently defined, encompasses several different Huron-Erie Lobe events and till sheets, which are difficult to correlate with one another, in various parts of northern and south-central Indiana. All these eastern-source tills are strikingly similar and frequently give way to bodies of outwash and lake sediment, making it highly problematic to trace individual events or deposits across the major region affected by the lobe. Thus, interpretations regarding the sequence of events as well as the character and continuity of the deposits they left, are best made at a more local scale, such as a county, and are often based as much on differences between landscapes affected by various events as they are on sediment properties. The following discussion simply highlights the major late Wisconsin events in Marion County, with a particular emphasis on natural and historical areas in the county where the impact of these events can readily be seen in the modern landscape. Additional details about the late Wisconsin deposits and events in the county, how they are manifested and identified, and the methods used to map them, can be found here.

Beginning between 21,000 and 22,000 years ago, late Wisconsin glaciers appear to have been active in or near Marion County almost continuously for the

next several thousand years, producing three major

Figure 12.

Left-Compact, dark brown T1 till overlies gray pebbly sand (outwash) in this exposure of late Wisconsin deposits along Buck Creek. The lowest

several inches of the till are sandier than the main mass because of incorporation of granular sediment from the underlying outwash. The till has a

knife-sharp basal contact and a strong fabric produced by the alignm