Age:Ordovician Type designation:Type locality: The Oneota Dolomite was named by McGee (1891, p. 331-333) for exposures along the Oneota River (now called the "Upper Iowa River"), Alamakee County, Iowa, where 200 to 300 ft (61 to 91 m) of dolostone overlies the Jordan Sandstone and underlies the New Richmond Sandstone (Droste and Patton, 1986). History of usage:Extended: In 1951, Willman and Templeton extended the use of the name to Illinois where the Oneota Dolomite overlies either the Gunter Sandstone or the Eminence Formation and is overlain by the New Richmond Sandstone (Droste and Patton, 1986).

Description:The Oneota consists predominantly of fine-to medium-grained dolostone but includes chert and, particularly near its base in some places, sporadic quartz sand and thin interbeds of green shale (Droste and Patton, 1986). The color is dominated by light shades of gray and brown, some medium-grayish-brown colors are present, and very light gray to white medium-grained dolostone several tens of feet thick generally marks the basal part of the formation (Droste and Patton, 1985, 1986). The chert in the Oneota is light colored and is variably vitreous, opaque, and tripolitic (Droste and Patton, 1985, 1986). Its color ranges from uniform to color-banded and oolitic-textured patterns (Droste and Patton, 1985, 1986). The chert is highly variable in abundance, ranging from small amounts of tripolitic quartz between well-formed dolomite rhombs to nodules and thin irregular beds in dolostone through zones several feet thick (Droste and Patton, 1985, 1986).

Boundaries:The Oneota conformably overlies the Potosi Dolomite and conformably underlies the Shakopee Dolomite except in northwesternmost Indiana where in the area of one well pre-Ancell erosion stripped completely the Shakopee and Oneota rocks, so that the Ancell rocks (St. Peter Sandstone) lie directly on the Potosi Dolomite (Droste and Patton, 1986). It is assumed, nevertheless, that in parts of this area yet untested by deep wells the Oneota unconformably underlies Ancell rocks (Droste and Patton, 1986). Correlations:The age of the Oneota is considered to be Ibexian (Ethington, Droste, and Rexroad, 1986), and the base of the Oneota defines the base of the Ordovician System in Indiana (Droste and Patton, 1986). The Oneota Dolomite of Indiana equates with the Gunter Sandstone and the Oneota Dolomite collectively of Illinois, with the lower part of the undifferentiated Prairie du Chien Group of Michigan, the lower part of the upper undifferentiated Knox Dolomite of Ohio, and the Gunter Sandstone and the Gasconade Dolomite of Kentucky (Droste and Patton, 1986).

|

|

Regional Indiana usage:

Illinois Basin (COSUNA 11)

Misc/Abandoned Names:None Geologic Map Unit Designation:Oo Note: Hansen (1991, p. 52) in Suggestions to authors of the reports of the United States Geological Survey noted that letter symbols for map units are considered to be unique to each geologic map and that adjacent maps do not necessarily need to use the same symbols for the same map unit. Therefore, map unit abbreviations in the Indiana Geologic Names Information System should be regarded simply as recommendations. |

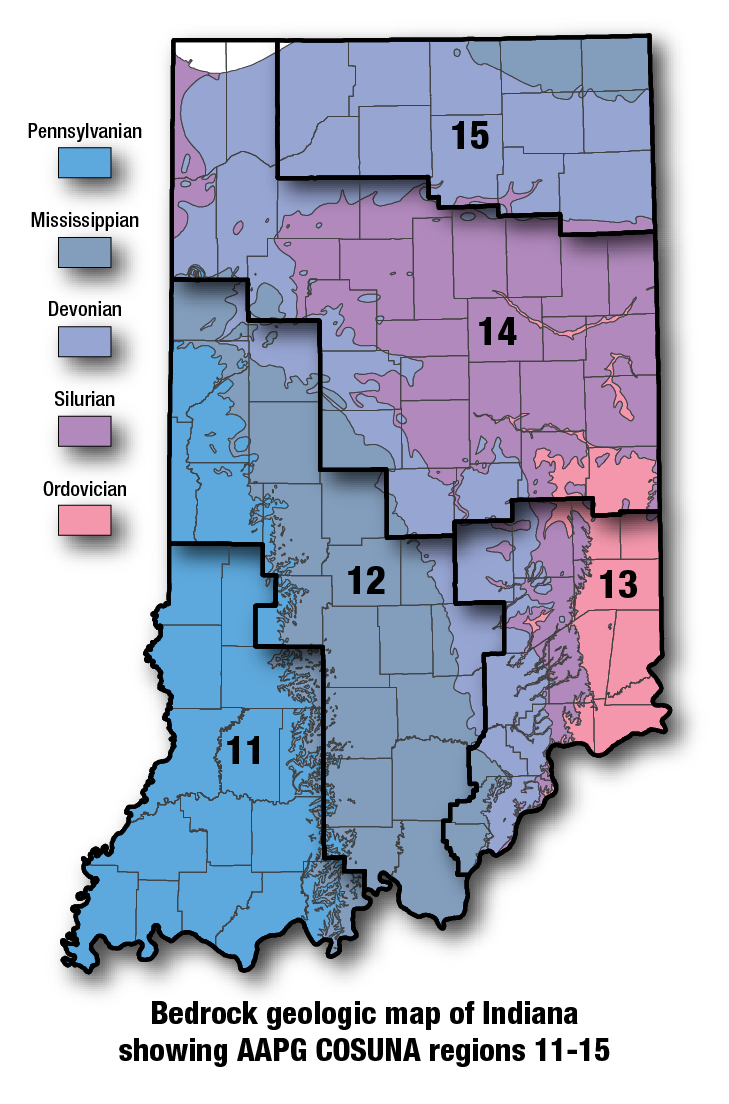

COSUNA areas and regional terminologyNames for geologic units vary across Indiana. The Midwestern Basin and Arches Region COSUNA chart (Shaver, 1984) was developed to strategically document such variations in terminology. The geologic map (below left) is derived from this chart and provides an index to the five defined COSUNA regions in Indiana. The regions are generally based on regional bedrock outcrop patterns and major structural features in Indiana. (Click the maps below to view more detailed maps of COSUNA regions and major structural features in Indiana.)

COSUNA areas and numbers that approximate regional bedrock outcrop patterns and major structural features in Indiana.

Major tectonic features that affect bedrock geology in Indiana. |

References:Freeman, L. B., 1949, Regional aspects of Cambrian and Ordovician subsurface stratigraphy in Kentucky: American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, v. 33, p. 1,655–1,681. Hansen, W. R., 1991, Suggestions to authors of the reports of the United States Geological Survey (7th ed.): Washington, D.C., U.S. Geological Survey, 289 p. Janssens, Adriaan, 1973, Stratigraphy of the Cambrian and Lower Ordovician rocks in Ohio: Ohio Geological Survey Bulletin 64, 197 p. McGee, W. J., 1891, Pleistocene history of northeastern Iowa: U.S. Geological Survey Annual Report 11, pt. 1, p. 189–577. McGuire, W. H., and Howell, Paul, 1963, Oil and gas possibilities of the Cambrian and Lower Ordovician in Kentucky: Lexington, Ky., Spindletop Research Center, [216] p. Shaver, R. H., coordinator, 1984, Midwestern basin and arches region–correlation of stratigraphic units in North America (COSUNA): American Association of Petroleum Geologists Correlation Chart Series. Willman, H. B., and Templeton, J. S., 1951, Cambrian and Lower Ordovician exposures in northern Illinois: Illinois State Academy of Science Transactions, v. 44, p. 109–125. |

|

For additional information, contact:

Nancy Hasenmueller (hasenmue@indiana.edu)Date last revised: October 28, 2014